Global headlines exploded last week with the G20 summit in Africa wrapping up on a note of urgency. Leaders pledged bold actions against soaring inequality and a crippling sovereign debt crisis hitting the world's poorest nations hardest. This fresh commitment spotlights a harsh truth that echoes through boardrooms and living rooms alike.

The old label of "Third World country" keeps surfacing in heated debates over migration and aid, now thrust into sharper focus by President Trump's stunning Thanksgiving announcement to permanently pause all migration from such nations. The move came mere hours after a deadly shooting in Washington D.C. claimed the lives of two National Guard members, an attack authorities are probing for possible ties to recent arrivals.

Trump's fiery social media post vowed to halt inflows "to allow the U.S. system to fully recover," igniting a firestorm of reactions from fury over lost opportunities to weary nods at security fears. In 2025, as trade tensions simmer and climate shocks intensify, grasping these dynamics feels more vital than ever. It reveals why some countries claw their way toward prosperity while others teeter on the edge, stirring a mix of frustration and fierce hope for change.

Donald Trump in the Oval Office as his migration pause sends shockwaves through global markets — a decision reshaping how the U.S. views developing economies and their financial futures.

The Origins of “Third World” — And Why the Term No Longer Fits

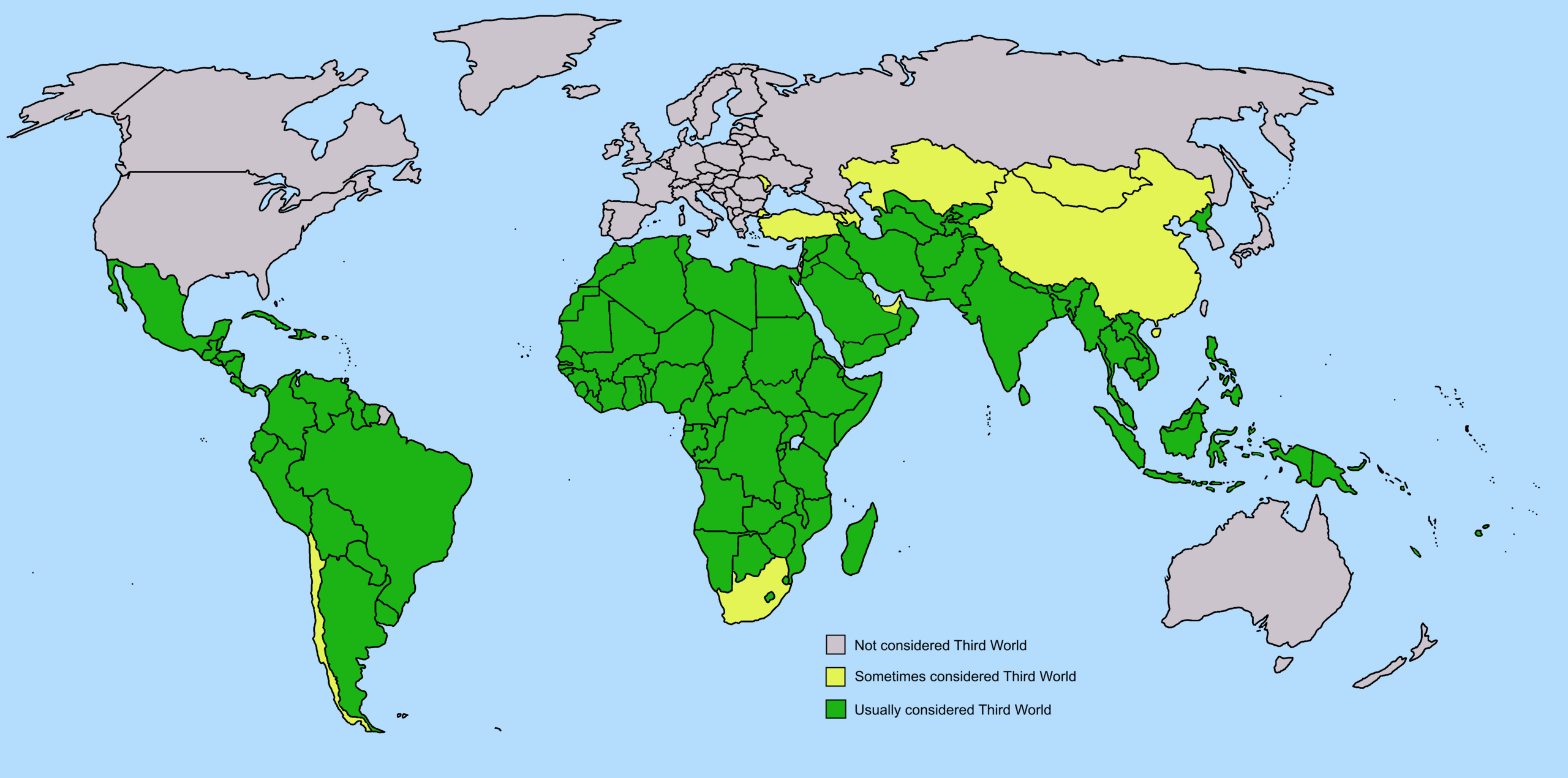

The phrase "Third World" burst onto the scene in the 1950s amid the Cold War's icy standoff. French demographer Alfred Sauvy dreamed it up to capture nations dodging alignment with either superpower camp. The First World meant the prosperous West, the Second World the Soviet sphere, and the Third World everyone else carving out independence. Back then, it carried no whiff of poverty or chaos. Over decades, though, as economic woes plagued many of those countries, the term twisted into a lazy catchall for struggle and stagnation. Economists today cringe at its use, calling it a relic that blinds us to nuance and breeds unfair stereotypes.

This outdated shorthand ignores the vibrant shifts reshaping global finance right now. According to analysis reviewed by Finance Monthly, modern labels hinge on hard data like output and resilience, not faded rivalries. They paint a picture of potential amid pain, urging investors and citizens to look deeper. Dropping the term frees us to celebrate breakthroughs in places once dismissed, while mourning the barriers that still bind too many.

The Financial Angle: How GDP Determines a Country’s Economic Standing

At the heart of a nation's global rank sits Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, the total value of goods and services produced within its borders over a year. This number tells a gripping story of vitality or vulnerability, influencing everything from job creation to family budgets. A surging GDP signals robust factories humming, tech startups thriving, and ports buzzing with exports that fund schools and hospitals. It draws eager investors betting on tomorrow's winners, fueling a virtuous cycle of innovation and uplift.

Nations often slapped with the "Third World" tag in casual talk share stark financial fingerprints that drag on their GDP. Low GDP per capita means scant economic pie sliced thin for each resident, breeding job scarcity and frayed safety nets. Heavy reliance on farming or raw commodities exposes them to wild price swings from distant markets, like coffee farmers watching harvests rot amid oversupply. Sparse factories and undiversified industries stifle broader growth, leaving economies exposed to shocks.

Towering debt-to-GDP ratios, sometimes exceeding 100 percent, force governments to divert funds from roads to repayments, trapping progress in a suffocating loop. Rapid population booms add pressure too, demanding jobs that a weak GDP simply can't conjure fast enough. These traits don't doom a country forever, but they demand bold, sustained reforms to ignite lasting momentum.

How Global Institutions Now Classify Economies

Powerhouses like the World Bank and IMF now slice the world by Gross National Income and GDP metrics, ditching ideology for cold facts. High-income economies boast per capita figures above $13,845, think Switzerland or Singapore with gleaming skylines and top-tier healthcare. Upper-middle peers like Brazil hover between $4,466 and $13,845, blending resource wealth with urban sprawl. Lower-middle nations, from India to Indonesia, straddle $1,146 to $4,465, where call centers and garment factories spark middle-class dreams. Low-income realms below $1,146 grapple with basics, their GDPs strained by conflict or isolation.

The United Nations sharpens this further with Least Developed Countries, or LDCs, a group of 44 nations marked by dire income, skimpy human assets like education, and fragility to crises. These modern stand-ins for the old "Third World" label span continents, from Africa's heartland to Pacific isles.

Here's the full roster as of late 2025: Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Kiribati, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Yemen, Zambia.

Investor radars like the MSCI Frontier Market Index spotlight smaller dynamos with explosive potential, such as Vietnam's assembly lines or Kenya's fintech boom. These aren't pity cases, they're high-stakes playgrounds where savvy bets can yield fortunes. Emerging markets bridge the gap, like Mexico or South Africa, blending risks with rewards that keep global portfolios humming.

A global development map reveals how nations are ranked today — a data-driven view that replaces outdated “Third World” labels with modern GDP-based classifications.

Why Some “Third World” Countries Graduate Into Emerging Markets — And Why Others Stay Stuck

Witness South Korea's phoenix rise from postwar rubble to Samsung's empire, its GDP per capita exploding from under $100 in 1960 to over $35,000 today through relentless education and export drives. Vietnam echoes this, its factories churning iPhones and sneakers to post 6 percent annual growth, luring billions in foreign cash. Bangladesh weaves textiles into a $45 billion export engine, lifting millions from mud huts to modest homes. India, once aid-dependent, now exports software worth hundreds of billions, its GDP trajectory a testament to services overtaking sweatshops.

Yet heartbreak lingers for those mired in low-income traps, where civil strife in Yemen or corruption in Haiti saps GDP before it blooms. Weak grids hobble factories, aid dependency dulls incentives, and barred trade doors seal isolation. Political turmoil and graft erode trust, scaring off the capital needed for liftoff. These nations aren't fated to fail, but breaking free demands iron-willed governance and global solidarity. Economist Jayati Ghosh captured the emotional stakes in a recent Project Syndicate piece, lamenting how "stagnant wages and eroding protections fuel an inequality crisis that tears at the social fabric we all share." Her words hit hard, reminding us that behind the numbers beat human stories of grit and grief.

Unlocking Futures: How G20's Fresh Debt Relief Push Could Supercharge GDP in Debt-Laden Nations

Sovereign debt, the money governments owe to lenders like the IMF or bondholders, looms as a silent killer for fragile economies. Picture it as a family's credit card bill ballooning unchecked, forcing skipped meals to cover interest. When debt swallows more than 60 percent of GDP, as it does in over half of LDCs per UN data, nations slash spending on clinics and classrooms just to stay afloat. This vicious spiral chokes growth, inflating costs and sparking unrest that ripples worldwide.

The G20's November 2025 pledges mark a game-changer, extending relief to 30 low-income countries facing $100 billion in repayments through 2026. This isn't charity, it's smart finance, freeing up cash for infrastructure that multiplies GDP by 1.5 to 2 percent annually in recipient nations, according to World Bank models.

Take an African exporter buried under $20 billion in loans, its cocoa fields idle for lack of roads. Debt forgiveness there could rebuild supply chains, boosting output 20 percent in two years and creating 50,000 jobs. Experts interpret this as a pivot toward sustainable lending, where relief ties to green projects, weaving climate resilience into growth. For consumers eyeing ethical investments, it means safer bets on funds targeting these rebounds, turning empathy into tangible returns while easing the quiet desperation of families worldwide.

Beyond the Basics: What Readers Like You Are Asking About Global Economies

Is Vietnam Still a Frontier Market in 2025, and What's Driving Its GDP Surge?

Vietnam holds firm as a frontier market powerhouse, its economy clocking 6.5 percent GDP growth this year amid factory expansions and tourism rebounds. U.S.-China trade frictions funneled $20 billion in new investments, shifting production lines for electronics and apparel. This influx not only pads export coffers but also trains a young workforce in high-tech skills, promising sustained leaps. For everyday folks, it translates to cheaper gadgets on shelves and rising remittances home, though challenges like urban overcrowding test the gains. Investors watch closely, as Vietnam's blend of low costs and stability could propel it to emerging status by 2030, reshaping supply chains forever.

How Does Climate Change Hit GDP Hardest in Least Developed Countries?

Climate shocks slash GDP in LDCs by up to 5 percent yearly through floods wrecking farms and droughts starving livestock, per IPCC estimates. These nations, often coastal or arid, lack buffers like insurance or reservoirs, amplifying losses that cascade into hunger and migration waves. A real-world parallel unfolded in 2024 when Cyclone Idai devastated Mozambique, erasing 2 percent of its GDP overnight and displacing 1.8 million. Recovery hinges on international funds, yet delays deepen inequality. Understanding this empowers consumers to back resilient brands, turning awareness into action that bolsters global stability and spares future generations the brunt.

Can Foreign Aid Ever Truly Lift a Country Out of Low-Income Status?

Foreign aid sparks debate, with studies showing it boosts GDP by 0.5 to 1 percent when funneled into education and health, but pitfalls like mismanagement can halve impacts. Success shines in Rwanda, where aid rebuilt post-genocide infrastructure, doubling GDP per capita since 2000 through targeted tech hubs. Pitfalls emerge in aid-dependent spots where it props corrupt regimes, stunting self-reliance. The key lies in conditional strings promoting transparency, as G20 talks now emphasize. For readers, this underscores choosing charities wisely, ensuring dollars foster independence over endless handouts and pave paths to thriving economies.