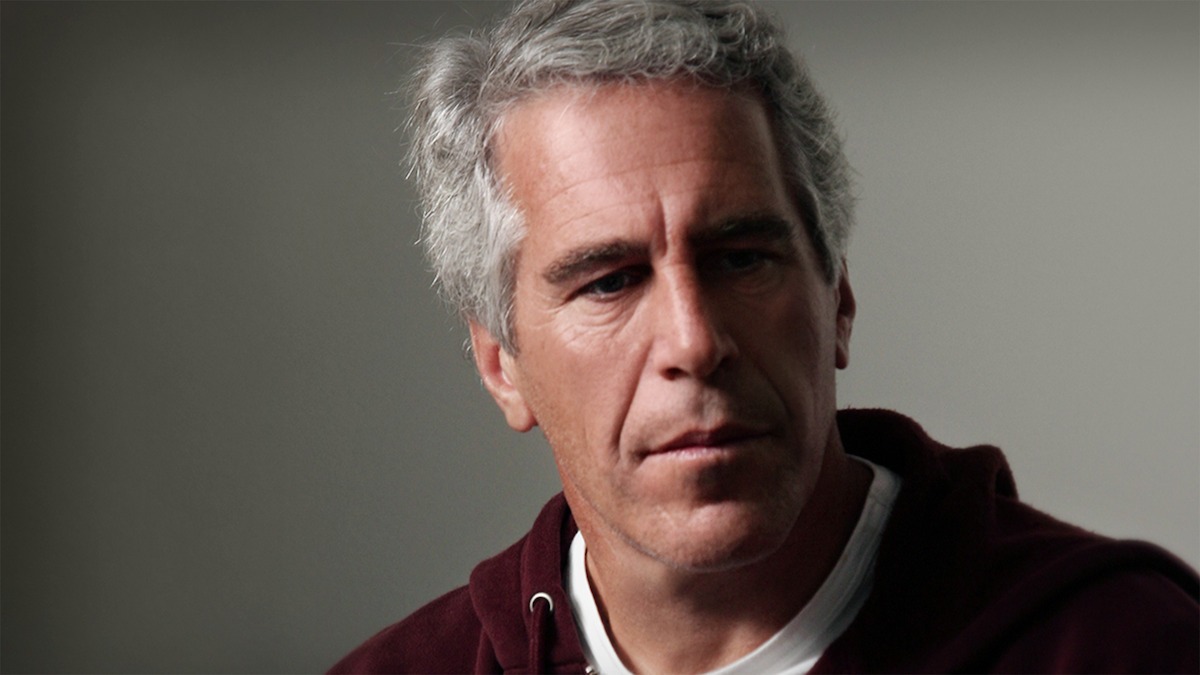

Epstein Files Release Exposes Victims’ Names — and Shifts the Case Before Any Court Ruling

The shift didn’t come from a courtroom ruling.

It came from a release.

A newly released set of Epstein-related court records briefly exposed the full names of at least 43 victims before redactions were applied, shifting the pressure around the case without any judge weighing in.

Once names are public, control doesn’t return easily.

A review by The Wall Street Journal found that the documents were made available in a form that allowed victims’ identities to be read unobstructed, raising concerns about how the disclosure process was handled and where accountability now sits.

The issue is procedural, not evidentiary.

No new charges were filed. No verdict reached. But the terrain still shifted.

For victims, the impact is immediate. Privacy that had been preserved through sealing orders and redaction protocols thinned out in a matter of hours. Names that had stayed confined to filings and exhibits re-entered the public domain, attached once again to a case many families have spent years trying to move past.

For prosecutors and court administrators, the pressure runs differently. Federal rules require identifying information about victims to be removed before public release, particularly in cases involving sexual exploitation. When that step fails, the question is no longer about transparency. It’s about exposure.

And exposure carries consequences long before any corrective ruling appears.

The timing makes the moment harder to absorb. The Epstein litigation ecosystem remains active, with civil claims and related proceedings still moving through the system. Nothing here was meant to accelerate. Yet the release forced responses from lawyers, families, and institutions that were not prepared to speak publicly again.

Silence becomes harder once names circulate.

The disclosure also changes how the broader case is consumed. Details that once sat behind procedural barriers are now being interpreted in public, even though interpretation is not the court’s job and resolution remains distant. That gap — between what is known and what has yet to be tested — is where pressure builds.

This is not unusual in high-profile cases. Outcomes are sometimes shaped less by findings of guilt or innocence than by administrative failures that alter leverage, timelines, and public posture well before trial.

Here, the concern extends beyond reputational harm. It raises a quieter institutional question: whether a system designed to protect victims can still be trusted to do so when disclosure controls fail at scale.

For now, there is no corrective order. No injunction restoring anonymity. No clear answer on whether the release can be contained.

What remains is a reopened wound and a system under scrutiny.

The case itself has not moved closer to resolution. But the environment around it has changed — and everyone involved is now operating with less privacy, less control, and more pressure than before.

Nothing has been decided yet.

But the room is no longer sealed.