What’s happening

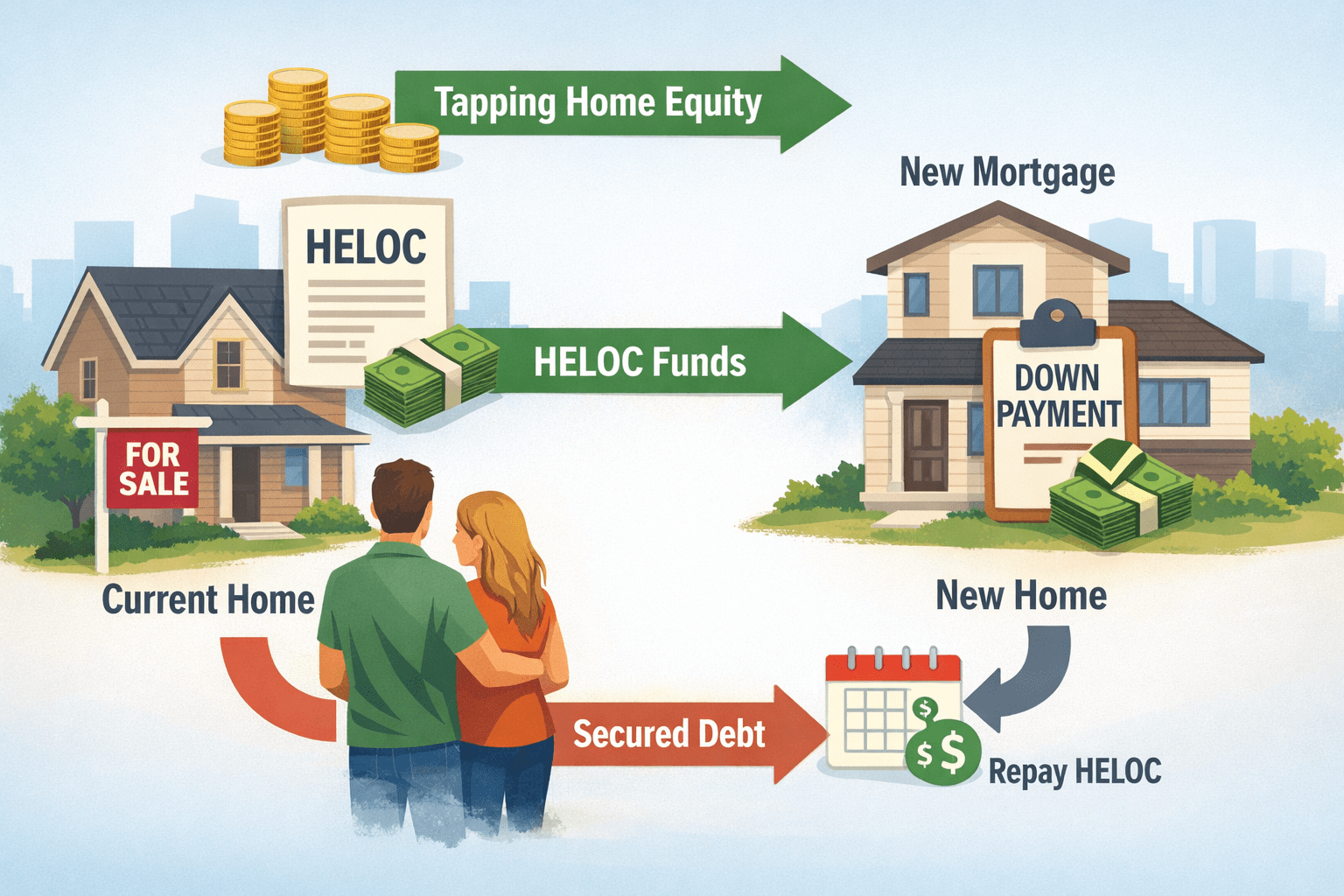

Homeowners with substantial equity are increasingly asking whether a home equity line of credit (HELOC) can be used to fund a down payment on a new property. The logic feels straightforward: borrow against existing equity, secure the new home, then repay the HELOC once the transaction settles.

Yet many borrowers report being told by banks that HELOCs are “not allowed” for that purpose — even as others say they’ve done exactly that without issue. The confusion stems from how lenders describe intended use versus how funds are treated once a HELOC is approved.

Why people are paying attention now

Higher interest rates, slower housing transactions, and tighter mortgage affordability tests have made short-term liquidity more important. For homeowners who are “asset-rich but cash-light,” HELOCs often look like a flexible alternative to bridge loans or forced asset sales.

At the same time, lenders have become more cautious about exposure, documentation, and repayment timing — which is why the same question can produce very different answers depending on who you ask.

Why banks ask what the money is “for”

When applying for a HELOC, borrowers are usually asked to state the purpose of the credit line. This is not just a formality. Lenders use declared purpose to assess risk profile, expected duration, and repayment behaviour.

HELOCs are typically priced and approved on the assumption that they will be used gradually — often for renovations, repairs, or ongoing household expenses — rather than drawn down in full and repaid quickly.

Using a HELOC as a short-term bridge can disrupt those assumptions, even if the loan is fully secured by property.

What happens after a HELOC is approved

Once a HELOC is established, it generally functions like a revolving credit account. Funds are accessible, repayable, and redrawable within the agreed limit, subject to interest and minimum payments.

At that stage, most banks do not actively monitor individual transactions. However, this does not mean usage is unrestricted in a legal or contractual sense. The governing factor is the loan agreement, not informal practice.

If a HELOC contract explicitly restricts certain uses — such as funding another property purchase while the original home is listed for sale — breaching those terms can technically trigger remedies, including cancellation or demand for repayment.

Why mortgage lenders care where a down payment comes from

The second layer of scrutiny often comes not from the HELOC provider, but from the new mortgage lender.

Mortgage underwriting rules typically require lenders to understand whether a down payment is:

-

From savings or equity

-

Gifted funds

-

Or borrowed money

Borrowed funds are usually allowed, but the associated debt must be included in debt-to-income (DTI) calculations. A HELOC used for a down payment can therefore reduce borrowing capacity or affect approval, even if it is permitted in principle.

This is why some lenders steer borrowers toward bridge loans, which are designed specifically for short-term property transitions and disclosed upfront in underwriting.

Where uncertainty and exposure remain

The grey area exists because HELOC policies vary widely by institution. Some banks prohibit specific uses outright. Others rely on disclosure and affordability checks rather than purpose-based restrictions.

What complicates matters further is that enforcement is often reactive, not proactive. Problems usually arise only if:

-

The borrower defaults

-

The property is sold unexpectedly

-

Or the lender discovers a contractual breach during a review

This gap between written rules and everyday practice is what fuels the perception of a “wink-wink” system — even though the legal exposure still exists.

How responsibility is typically assessed

Responsibility in these situations does not hinge on what “everyone does,” but on what was agreed in writing, how the funds were disclosed, and whether repayments remain sustainable.

Banks retain discretion in how strictly they enforce usage terms, especially when loans are performing. Mortgage lenders, meanwhile, focus on affordability, transparency, and risk stacking — not moral judgments about borrowing strategy.

Outcomes depend heavily on documentation, timing, and institutional policy rather than any single universal rule.

What hasn’t changed

A HELOC is still secured debt. Using it increases leverage, affects cash flow, and links multiple properties financially. That reality exists regardless of how common or uncommon a particular strategy may be.

What has not changed is that lenders prioritise repayment certainty over intent — and reserve the right to reassess if circumstances shift.

Open questions that remain

As housing markets stay tight and financing structures grow more complex, borrowers are left navigating overlapping rules that were never designed to align perfectly.

The unresolved tension is not whether HELOCs can be used this way in practice, but how much risk borrowers are willing to carry when flexibility collides with formal loan terms.