Across the UK, large numbers of homeowners are approaching the end of fixed-rate mortgage deals agreed years ago, often when interest rates were far lower.

As those deals expire, borrowers must refinance into a very different rate environment, regardless of whether their household finances have changed.

People are paying attention because this is not a gradual shift. Around 1.8 million fixed-rate mortgages are due to end within a single year, concentrating financial pressure into a short window and raising broader questions about how mortgage resets ripple through households, lenders, and the wider economy.

Why this matters now for households and lenders

Fixed-rate mortgages delay the impact of interest-rate changes. While rates rose sharply after 2021, many borrowers were insulated until their fixed terms ended.

When large numbers reset together, that delayed impact arrives at once. Monthly payments can jump suddenly, affecting household spending and savings at scale rather than one borrower at a time.

How mortgage resets actually unfold over time

Mortgage stress does not arrive on a single day. Pressure tends to appear in stages that are easy to miss.

Borrowers often lock in new offers months before expiry, making decisions with incomplete information. Higher payments usually begin weeks later, and the full effect on household budgets can take months to surface as savings buffers thin.

Why many borrowers end up on higher rates by default

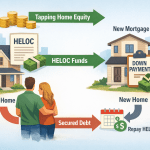

When a fixed term ends, loans typically move onto a lender’s standard variable rate unless action is taken. In theory this is temporary, but in practice many people stay longer than expected.

Some assume lenders will move them onto a reasonable alternative. Others delay because they fear failing affordability checks, or because the paperwork feels overwhelming during periods of uncertainty. These behavioural defaults help explain why higher rates persist even when options exist.

What’s driving the pressure behind these resets

Interest rates rose rapidly as central banks responded to inflation, including repeated increases by the Bank of England. Fixed-rate deals agreed earlier reflected a very different cost of money.

Although rates have since stabilised, mortgage pricing still reflects higher funding costs than in the past. The gap between old fixed payments and new offers is what many households are now absorbing.

Where exposure is uneven across households

Not all borrowers face the same adjustment. Single-income households and self-employed borrowers often encounter tighter affordability limits than those with stable dual incomes.

Those closer to the end of their mortgage term may experience the impact differently from borrowers earlier in the repayment schedule. These variations shape how pressure shows up across regions and demographics rather than producing a uniform outcome.

How refinancing waves strain the system in practice

Refinancing is not frictionless. Lenders must process valuations, affordability checks, and underwriting decisions, often at the same time for large numbers of borrowers.

Capacity limits and administrative backlogs mean households cannot all refinance smoothly at once. This helps explain why stress can cluster even without a sharp rise in unemployment or forced selling.

Where oversight usually sits

Mortgage markets operate within regulatory frameworks that set lending standards and affordability tests, but outcomes are not automatic.

How refinancing pressure plays out depends on timing, household circumstances, lender discretion, and market conditions. Oversight focuses on system stability rather than guaranteeing individual results.

What remains unresolved

The current wave of mortgage resets highlights a structural feature of fixed-rate lending: short-term stability can create concentrated pressure later.

Whether future mortgage markets rely as heavily on fixed-term cliffs, or move toward smoother transmission of rate changes, remains an open design question rather than a settled outcome.